Time Trials

03 May 2023The Handex is a novel keyboard so it requires new learning.

I’ve been going through the process over the last month, so I want to record the issues I’ve faced and how I’ve overcome them.

I also want to plot the trajectory of my performance improvement so that we can estimate the viability of using a Handex device in many novel scenarios and use cases.

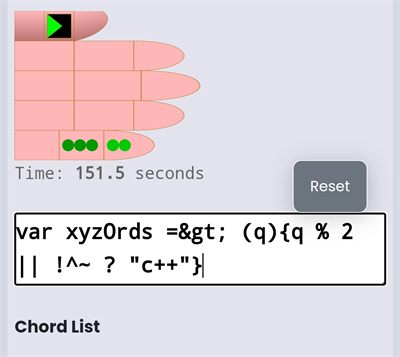

One of my biggest performance improvements came from improving the training UI.

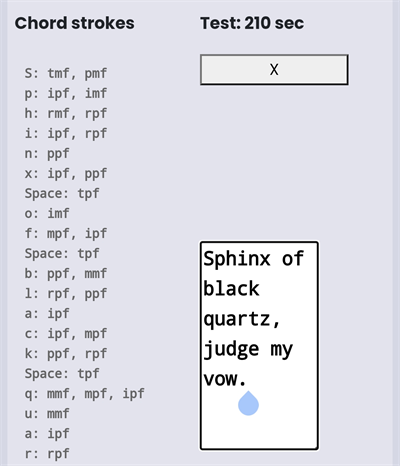

Initially, I indicated each finger action by a three-letter code. The code was suitable for internal finger-action character mapping, but it took way too long to interpret when trying to execute the finger actions

I made incremental improvements to the UI almost every time I used it. I found it very useful to indicate the next character to be typed, rather than performing the string bijection by eyeball on-the-fly.

Each of the changes trimmed the cognitive processes I need to perform and my speed performance improved incrementally.

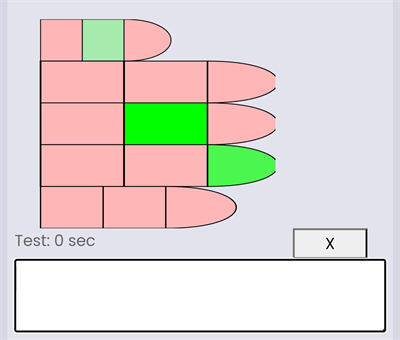

I was using SVGs for the hand images and I tried indicating order by color-coding the background with various shades of green.

I thought of using a color convention, like green for start and red for stop, but making a finger segment red is also the conventional indicator of blood. I didn’t want to launch a new UI with bloody fingertips everywhere and decided it was better to avoid such connotations.

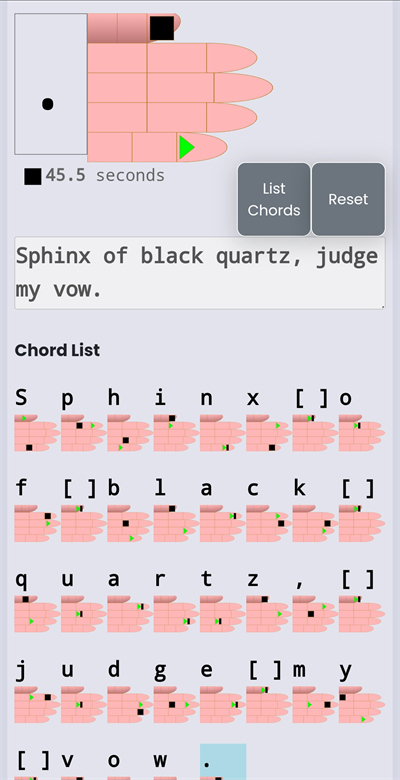

I decided black would be the best color for stop, and that made me think of the start/stop shapes from the old cassette tape decks that continued to be used for CDs and now YouTube and online video players.

With the action glyphs in place I started to see significant time improvements.

I also realized I could remove the three-letter character list that I had put so much effort into. :-( :-)

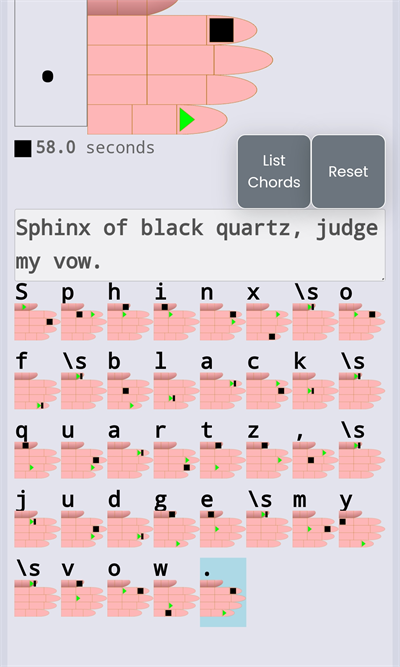

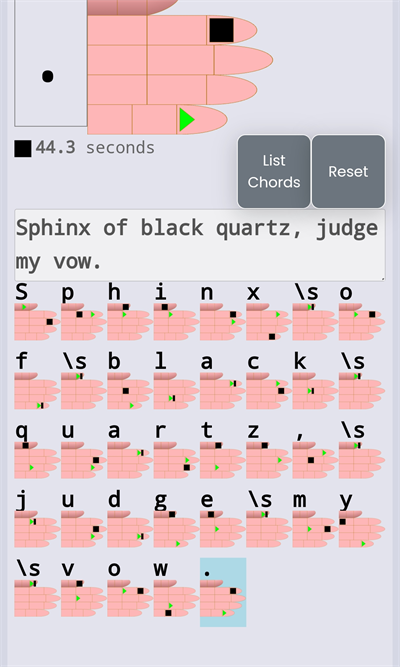

After removing the three-letter chord clutter, I realized that I had all the chord images already assembled, so I could just display each one in the chord. That provided the full-chord-view that the three-letter list only pretended to do but wasn’t very useful for.

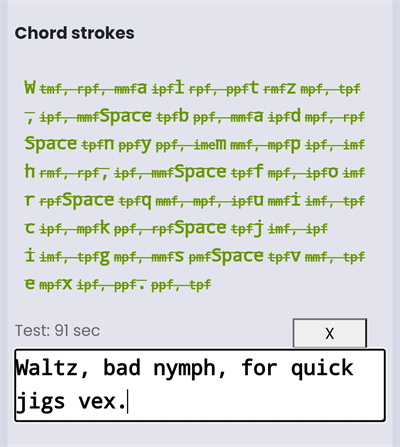

I can look at the next chord while finishing the chord I’m on, which isn’t possible with the big hand-chord at the top which only displays one next chord.

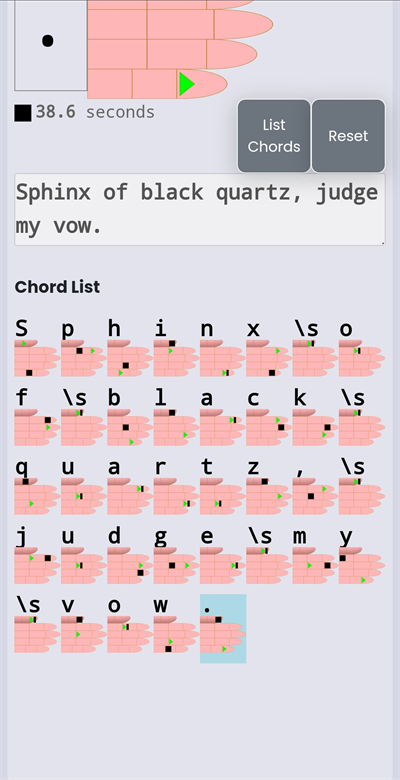

Now I was seeing some significant speed improvements, so I also cleaned up the clock a bit.

With little practice, maybe a full hour of practice, I was able to get the Sphinx pangram time down into the 30-second range.

Around the same time, I was able to improve the PSoC logic device code. With the addition of a 10ms delay in my pin-polling switch de-bouncer, I was able to reduce sticky-key repeat and also solve a problem I was having with longer chords of 4+ finger actions per chord.

Those improvements improved reliability. Reliability improvements are interesting because they aren’t immediately apparent. The result is just a general feeling of a nicer user experience. My training sessions just became nicer and less annoying.

That feeling of niceness was a little disconcerting. It probably meant I was no longer pushing myself far enough fast enough, so I decided to refactor the key mapping.

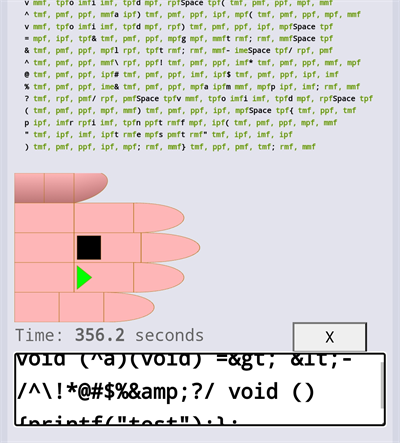

I decided that my next target would be Vim editing, which means I need the home-row keys to be single-stroke, or single finger-action.

This is good. This was always where this was going to go. A one-handed keyboard implies the need for keyed navigation and editing, as well as command-line arguments.

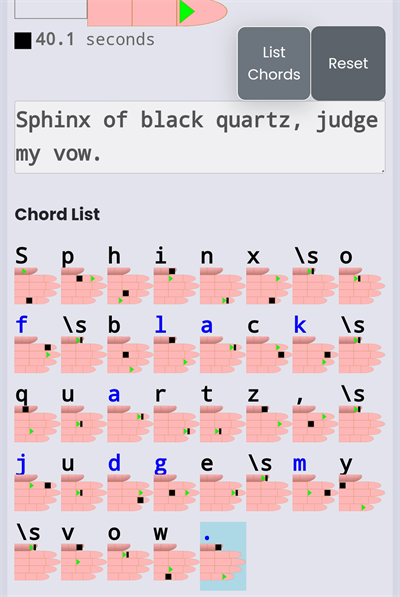

The first step was just to hightlight Vim navigation keys.

Then I went ahead and assigned ‘asdf’ to the proximal flection of each non-thumb finger, and ‘jkl;’ to each metacarpal interphalangeal joint flexion.

I was a little surprised to see how much damage the key remapping did to my time performance, since I have not yet memorized character-chord mappings.

It looks like the new mappings, even though they are faster for common characters, require learning new hand-chord glyphs, and the glyph-to-finger-action mapping that takes place in mind-body automation requires new learning.

Enough of the glyph-recognition training is translatable to the new chord-character mapping that I’ve been able to recover some time performance quickly.

All of these improvements occurred prior to my memorizing more than about 5 characters. I probably don’t even use the memorized characters when I’m reading the glyphs. It’s equivalent to having to type by looking at images of finger postions.

Of course, that is slower than memorized character-finger-action mappings that all speed-typists have memorized and automatized into reflexive habituation.

These time trials were also conducted using sub-sufficient tactile switches which are creaky and require variable force depending on various environmental conditions. Some of the switches seem to require extra force before they get warmed up or something, for instance.

These are just some of the observations that go into estimating future use case viability for the Handex. How many ways will an improved Handex be useful? The forgoing improvements seem to indicate a vast new area which the Handex can be developed into with great advantage.